Ali the contact lens maker

I thought I’d give it one last try. It had just gotten dark and I was sure nobody would pick me up anymore, but I had nothing to loose, except camping next to a little river below the roundabout, amidst the big, barren hills of the Ayrshire lowlands.

So I stuck out my thumb and held up my sign saying “The South”. I was just so glad to be on the road, breathe the fresh air and look into the night sky; to watch the rabbits running between the bushes on the central part of the roundabout, to smile at the people in passing cars, who looked at me as if saying: ‘Look at him! He must be nuts!’. It felt good to be standing there. I didn’t mind the cold and didn’t think it was dangerous to hitchhike after dark. I felt relieved, because I didn’t have anything in particular to do and had two weeks before university started in St. Andrews. I had left the flat I only found two days earlier and only moved into that morning and decided to hitchhike to Cornwall, where my girlfriend was working. She’d told me stories about sunshine, beaches, surfing and little quirky villages on gorgeous coastlines, so that, apart from the prospect of seeing her again after 2 ½ months, I was really looking forward to Cornwall.

* * *

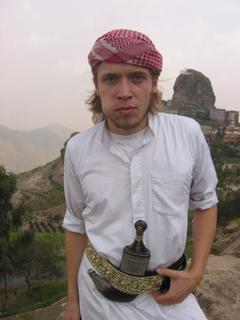

I had only returned from the Yemen a little more than a week ago and still found myself responding with “Aywa” and “Shukran” or waiting for someone to call me “Selim”. A lot had happened in the few days since I’d left the Yemen. On Tuesday morning I was still walking through misty mountains in the Manakha district of Northern Yemen. On Wednesday morning I flew into Munich airport. Thursday early morning I left Bavaria in my Polo, heading for a ferry in Belgium and Friday noon that ferry arrived (with me on it) in Rosyth, north of Edinburgh, in Scotland. Then I spent three days in the library in St. Andrews, reading about the Ottoman empire and the modern history of Egypt and Palestine, then four days finding a flat, catching up with a few friends and bidding on old chairs and dining tables in McGregor’s auction house. Now it’s Saturday, I’ve got a flat (when everybody else already had theirs at the end of March) and have already moved part of my stuff in, but felt a need to leave again, before being confined to that space for longer than I would probably wish to look forward to, reading, studying and desperately cramming Arabic vocabulary.

* * *

Not even ten minutes later, as I was still pondering over my new flat, a white “enterprise”-hired van stopped and the driver said he was going all the way to Southampton that night – I couldn’t believe my luck – I was only about an hour south of Glasgow and had hoped to get maybe down to Carlisle before having to pitch my tent, but now I had a chance to go all the way to the South coast of England before the sun would rise the next morning. I didn’t hesitate for a minute and jumped in. I looked back at the petrol station on the other side of the roundabout as we drove off, then made myself comfortable, took my shoes off and introduced myself to the driver. His name was Ali and he said he was Afghani – I was euphoric and asked him in Arabic, whether he spoke any Arabic, but then realised that my enthusiasm had impeded on my rational thinking: not many people speak Arabic east of Iraq. But Ali spoke at least five other languages, including Farsi, Pashtu, Urdu and two others that I’d never heard of. I tried to dig out some Farsi, but found it completely over-layered by the Arabic I had learned in the Yemen – I was incapable of forming even one cohesive sentence. It’s amazing how something that was so familiar to you only two months ago can be so overshadowed by something new, something more recent.

* * *

Anyway, although hitchhiking with an Afghani in a big white van after darkness might sound scary to some people, Ali turned out to be a wonderful acquaintance. He had a masters degree in International Relations (!) from a university in Pakistan, where he had lived most of his life, but because he cleverly lied to British Home Office officials when he came to seek asylum in the UK six years ago, telling them that he’d never been to Pakistan, he couldn’t make much use of his degree and thus worked in the biggest European contact lens factory on a construction line.

He said: “Because of that one lie, now I can do whatever I want, in Britain at least, but every time I think of that moment, I feel shy – I feel shame – shameful, I regret that, I think it was wrong. You know, I have work permit, social security number, I pay taxes, insurance, rent, I don’t claim benefits, I don’t work illegally, I have car and flat, but I feel shame.”

I was astonished.

I tried to persuade him that he didn’t do anything wrong – he didn’t harm anybody, his lie had no negative impact on anybody’s life or on any system or anything, the official he lied to probably doesn’t even remember him or even cared whether he was saying the truth or not, that he isn’t abusing the state or the welfare system here, like some others are and so on, but he didn’t care: it was shameful, he said.

Almost more amazing, though, was how he got an Afghani passport to begin with, in order to then be able to pretend never to have been in Pakistan, because having left Afghanistan at the age of three, he now only had Pakistani citizenship – not a good one to have if you want to emigrate to Britain. So it wasn’t till he’d arrived in the UK: He went to the Afghani consulate in London with nothing but £60 in his pockets – no papers, no documents, no ID. Half an hour later he walked out of there with an Afghani passport. I didn’t believe him: “How did they know you were Afghani?” “I told them” he said, “we speak the same language, so they knew.” I laughed and was glad to know that there were places in the world where people still trust your word!

* * *

When I told him that I studied Arabic, he asked whether I was planning on becoming a Muslim (a question I got asked many times a day in the Yemen). I denied and inquired about his religion.

“Muslim” he said, so I sarcastically asked, whether we’d have ‘pray-stops’ on our way down south.

“No, I’m a bad Muslim, I only carry the name – I think religion is POISON.”

“Why?” I asked.

“In Pakistan, where I grew up, society is so dominated by Islam and it has make life so difficult – people are killed there every day in the name of religion – it is poison.”

I thought it an interesting alternative to Marx’s famous quote.

* * *

Ali left Portsmouth at 6am that morning, with the van full of his friends’ possessions, a Chinese couple who were going to study in Edinburgh. He drove their stuff up, helped them unpack and now he was on his way back down again. A total of 1000 miles and he wouldn’t be at home till about 4 am. – “I like driving – I don’t get tired” he said. I trusted him and went to sleep.

* * *

At 3am he dropped me off south of Oxford, near Andover, where the A34 meets the A303, which I was going to continue westwards on the next morning. I stood on the gravel under the motorway-bridge watching his van’s red backlights disappear into the night, then I shouldered my backpack, took out my torch and walked away from the roads for a while until I found a soft, grassy field to pitch my tent in. A strange and amazing day came to an end. After only three rides, I had crossed almost the entire country, from Eastern Scotland to Southern England. My first ride from Dundee was the father of a boy who studied Russian at St. Andrews (the flick-knife I’d brought with me for protection fell out of my pocket in his car and finding it probably caused him a bit of a shock – I think they’re not strictly legal in the UK), the second one was a geographer, working for the planning department in Dumfries, who’d been to Southern Yemen on a geographical mapping trip 15 years ago and the last one was Ali, the friendly and humble Afghani contact-lens maker with a degree in International Relations.

What a wondrous and wonderful world!